Akar Sejarah dan Evolusi Guangzhou Hui Su (Ukiran Plaster)

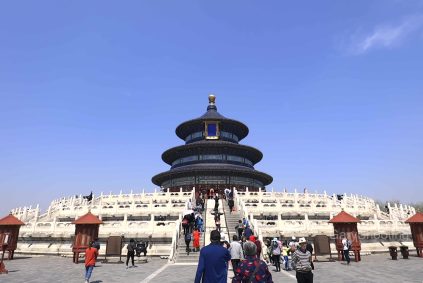

Guangzhou Hui Su, juga dikenali sebagai “Hui Pi” (batching plaster), ialah seni rakyat tradisional yang berakar umbi di wilayah Lingnan di Wilayah Guangdong, China. Sejarahnya boleh dikesan kembali ke Dinasti Tang, dengan bukti terdokumentasi terawal yang ditemui di Kuil Zengcheng Zhengguo, terbina dalam 1197 semasa Dinasti Song Selatan, yang mempunyai ukiran plaster “permatang perahu naga.” Bentuk seni ini berkembang pesat semasa dinasti Ming dan Qing, menjadi sebahagian daripada hiasan seni bina di dewan nenek moyang, kuil, dan kediaman kaya di seluruh Guangzhou dan kawasan sekitarnya, termasuk Zengcheng dan Conghua.

Perkembangan Hui Su berkait rapat dengan peranan Guangzhou sebagai pelabuhan utama di Laluan Sutera Maritim. Kemasukan kayu keras seperti rosewood dan padauk dari Asia Tenggara menyediakan tukang dengan bahan berkualiti tinggi, manakala iklim subtropika lembap di bandar ini memerlukan tahan lama, hiasan tahan cuaca. Tidak seperti arca seramik atau kayu, Hui Su tidak memerlukan tembakan, membenarkan pembinaan di tapak dan kebolehsuaian kepada struktur seni bina yang kompleks. Fleksibiliti ini, digabungkan dengan ketahanannya terhadap asid, alkali, dan perubahan suhu, menjadikannya sesuai untuk persekitaran tropika Guangzhou.

Simbolisme Budaya dan Ciri-ciri Seni

Kepelbagaian Tematik dan Penceritaan

Guangzhou Hui Su terkenal dengan repertoir tematiknya yang kaya, yang merangkumi cerita mitologi, naratif sejarah, dan adegan kehidupan seharian. Contohnya, Dewan Moyang Chen Clan, karya seni bina Lingnan, mempamerkan karya Hui Su yang menggambarkan cerita daripada Romantik dari Tiga Kerajaan dan Margin Air, serta adegan ulama dan abadi. Gubahan berbilang panel ini sering menyampaikan pengajaran moral atau meraikan kebaikan seperti kesetiaan dan ketakwaan anak, selaras dengan fungsi pendidikan balai nenek moyang.

Imejan Simbolik dan Motif Bertuah

Artis Hui Su kerap menggunakan imej homofonik dan simbolik untuk menyatakan rahmat. kelawar, dilafazkan “fu” dalam bahasa Cina, melambangkan kebahagiaan, manakala pic mewakili umur panjang. Gabungan seperti lima kelawar mengelilingi watak Cina untuk “shou” (panjang umur) menyampaikan “Lima Rahmat Mengkelilingi Panjang Umur.” Motif biasa lain termasuk singa (melambangkan kuasa), pokok pain (daya tahan), dan peonies (kemakmuran), semuanya diberikan dengan bentuk yang dibesar-besarkan untuk meningkatkan daya tarikan visual.

Integrasi Lukisan dan Arca

Hui Su ialah bentuk seni hibrid yang menggabungkan arca tiga dimensi dengan lukisan dua dimensi. Artisan menggunakan alatan seperti “hui chi” (kulir plaster) untuk membentuk lapisan plaster berasaskan kapur, bermula dengan yang kasar “cao gen hui” (plaster akar jerami) untuk struktur, diikuti dengan lebih halus “zhijinhui” (plaster pulpa kertas) untuk kelancaran, dan akhirnya “se hui” (plaster berwarna) untuk perincian. Langkah terakhir melibatkan pengecatan dengan pigmen semulajadi yang diperoleh daripada mineral dan tumbuhan, mencipta warna terang yang tahan luntur.

Ketukangan dan Teknik

Penyediaan Bahan dan Reka Bentuk Struktur

Penciptaan Hui Su bermula dengan penyediaan plaster, yang melibatkan mencampurkan kapur dengan air, jerami padi, dan pes pulut, kemudian menapai campuran selama berminggu-minggu untuk meningkatkan ketahanan. Artisan membina rangka rangka menggunakan paku buluh, wayar besi, dan jalur kuprum untuk menyokong lapisan plaster. Rangka kerja ini mesti mengambil kira pengagihan berat dan kelengkungan permukaan seni bina, memastikan kestabilan dan umur panjang.

Binaan Berlapis dan Ukiran Perincian

Proses memahat berjalan secara berperingkat, dengan setiap lapisan plaster digunakan dan diukir secara berurutan. Artisan memberi perhatian kepada faktor persekitaran seperti kelembapan dan suhu, kerana ini menjejaskan masa pengeringan dan keplastikan plaster. Teknik seperti “tong diao” (melalui ukiran) mencipta kesan separa telus, membenarkan cahaya menapis dan mengeluarkan bayang-bayang yang rumit. Kaedah ini sering digunakan dalam tingkap kekisi dan skrin hiasan, menambahkan interaksi dinamik cahaya dan ruang pada bangunan.

Pemeliharaan dan Penyesuaian

Walaupun kepentingan sejarahnya, Hui Su menghadapi kemerosotan semasa Dinasti Qing lewat dan Revolusi Kebudayaan, apabila banyak karya dimusnahkan. Walau bagaimanapun, usaha baru-baru ini oleh kerajaan China dan organisasi kebudayaan telah menghidupkan semula minat dalam bentuk seni ini. Inisiatif termasuk penubuhan Guangzhou Hui Su Cultural Development Co., Ltd., yang menggalakkan penyelidikan dan pendidikan, dan penetapan Hui Su sebagai warisan budaya tidak ketara negara di 2008. Tukang moden juga meneroka aplikasi inovatif, seperti menggabungkan Hui Su ke dalam reka bentuk dalaman kontemporari dan pemasangan seni awam, memastikan kaitannya dalam abad ke-21.