Guangzhou’s Traditional Funerary Customs: A Cultural Tapestry of Rituals and Beliefs

Racines historiques: Des rites anciens aux adaptations du Lingnan

Guangzhou’s funerary traditions trace back to the Zhou Dynasty’s Six Rites (Liu Li), which formalized mourning protocols. Par la dynastie Qing, these rituals merged with Lingnan folk beliefs, creating a unique blend of Confucian formalism and local superstitions. Par exemple, la pratique de Guo Huopen (crossing a fire basin) during weddings evolved into a funerary ritual to ward off evil spirits. Historical texts like the Guangzhou Fu Zhi (Guangzhou Annals) document how families in the 19th century adhered to strict timelines for burials, often consulting geomancers to select auspicious dates.

During the Republic of China era, urbanization and Western influences introduced simplifications. Civil weddings and secular ceremonies began replacing elaborate rites, yet core traditions persisted. Par exemple, le Da Li (betrothal gifts) cérémonie, once involving symbolic items like dragon-phoenix cakes, transformed into a pre-funeral ritual where families exchanged tokens of respect. This duality reflects Guangzhou’s ability to preserve heritage while adapting to modernity.

Rituels de base: Symbolisme et liens familiaux

Bathing the Deceased and the Mai Shui Rite

Before encoffinment, families perform the Mai Shui (buying water) rituel. The eldest son or a proxy travels to a river with a copper coin, “purchasing” water to bathe the deceased. Cet acte, recorded in 19th-century folk accounts, symbolizes purifying the soul for its journey. The water is poured over the body using a red cloth, mimicking a bath, while relatives chant prayers. Variations exist: in Panyu District, families sing Mai Shui Ge (Buying Water Song) as they wash the deceased, blending lamentation with folklore.

Encoffinment (Ru Zang) and Clothing Etiquette

The deceased is dressed in Shou Yi (funerary garments), traditionally made of silk and dyed in somber hues like indigo or brown. Red and pink are avoided, as they symbolize joy. The number of layers follows the odd-number rule: 11 upper garments and 7 lower garments, though some families use 7 et 5 pieces respectively. UN Ji Ming Zhen (rooster-shaped pillow) filled with feathers is placed under the head, believed to aid the soul’s awakening in the afterlife. During encoffinment, a red thread is stretched across the coffin to align the body correctly, a practice rooted in geomantic principles.

Gender-Specific Rites: Fen Shu et Che Fu

Marital status influences posthumous rituals. If a deceased woman’s husband survives her, he places a red flower in her hair (Si Zai Fu Qian Yi Zhi Hua), symbolizing eternal love. A wooden comb is then snapped in half: the shorter piece buried with her, the longer kept by the husband (Fen Shu or “parting the comb”). For men, only the comb is broken. En plus, the husband’s pants are placed in the coffin, later retrieved by the son (Che Fu or “pulling wealth”), symbolizing the transfer of prosperity.

Évolution moderne: L'innovation rencontre la tradition

Collective Mourning and Cultural Revival

Depuis 2020, Guangzhou has promoted eco-friendly burials, yet traditional rituals persist in adapted forms. Collective weddings, now incorporating funerary elements, are held in ancestral halls like the Liwan District Heritage Center. These events feature reenactments of Mai Shui et Ru Zang, blending historical accuracy with modern sustainability. Par exemple, biodegradable Shou Yi made from organic cotton are used in some ceremonies, reflecting environmental awareness.

Digital Engagement and Cultural Preservation

Museums such as the Guangdong Museum of Folk Culture showcase artifacts like Mai Shui Dou (water-buying basins) et Ji Ming Zhen. Interactive exhibits allow visitors to simulate rituals, while social media campaigns encourage young people to share their experiences. UN 2023 WeChat initiative, “Preserving Our Roots,» collected stories of funerary customs from elderly residents, creating a digital archive accessible to researchers and the public.

Adaptations régionales et routes symboliques

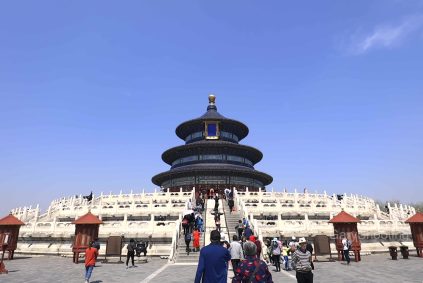

Guangzhou’s funerary routes remain steeped in symbolism. Les cortèges traversent souvent des rues portant des noms de bon augure comme Jixiang Lu (Route de la chance) ou Baizi Lu (Route des Cent Fils). In Shawan Ancient Town, District de Panyu, families reenact historic rituals such as the Ganzhu Lang Li (cérémonie d'élevage de porcs), where a piglet is presented to symbolize abundance. These adaptations highlight the flexibility of Guangzhou’s traditions, which evolve without losing their cultural essence.

Une tradition vivante: From Ancestral Rites to Contemporary Practice

Guangzhou’s funerary customs are a testament to the city’s ability to honor its past while embracing change. Que ce soit grâce à la préservation méticuleuse de Mai Shui ou la fusion créative de l'ancien et du nouveau, ces rituels continuent d'unir les familles, celebrate life, and sustain cultural identity. À mesure que la ville évolue, its funerary traditions remain a vibrant expression of Lingnan heritage—a blend of history, symbolisme, et l'esprit de communauté durable.