Guangzhou’s Lingnan Garden Culture: A Fusion of Tradition and Innovation

Historical Roots: From Imperial Palaces to Merchant Estates

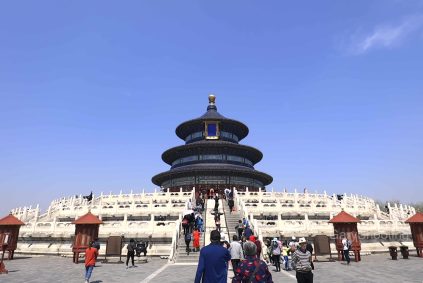

Lingnan gardens in Guangzhou trace their origins to the Western Han Dynasty’s Nanyue Kingdom (204–111 BCE), where the earliest known royal garden—a stone-lined pool and curved canal system—was unearthed in modern-day Yuexiu District. This site, featuring ice-cracked sandstone slabs and an intricate water network, reflects early attempts to harmonize artificial structures with natural landscapes. By the Five Dynasties period (907–960 CE), the Southern Han Dynasty expanded this legacy with the Yaozhou “Medicine Isle” in present-day Education Road, a royal garden centered around a lake with nine mythical stones symbolizing celestial bodies. Though partially submerged by urbanization, eight of these stones remain, marking China’s oldest surviving garden rockery.

The Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) witnessed a surge in private gardens, particularly among wealthy Thirteen Factories merchants in Guangzhou’s Xiguan district. These “merchant gardens,” such as the fabled Haishan Xianguan, blended Chinese symbolism with Western influences, featuring marble bridges, multi-story pagodas, and avian pavilions. While most were destroyed during the Second Opium War (1856–1860), their legacy inspired the Four Great Lingnan Gardens recognized today: Qinghui Garden (Shunde), Liang Garden (Foshan), Yuyin Shanfang (Panyu), at Keyuan (Dongguan).

Architectural Features: Space, Light, and Material Innovation

Lingnan gardens are distinguished by their “building-around-courtyard” layout, where structures encircle open spaces to maximize ventilation and natural light—a response to Guangzhou’s subtropical climate. Halimbawa, Yuyin Shanfang, a 2,000-square-meter garden built in 1867, employs a “hidden from view, revealed upon entry” design, using moon gates and lattice windows to frame fragmented views of ponds and rockeries. Its signature “Five-Layered Rockery” stacks limestone into a vertical labyrinth, symbolizing mountains amid flat terrain.

Water plays a central role, with gardens like Keyuan integrating geometric pools and winding streams to create dynamic reflections. The “Nine-Bend Bridge” in Keyuan, a 3.3-acre masterpiece, connects pavilions, studios, and flower beds, embodying the principle of “borrowed scenery”—where distant views are framed by architectural openings.

Materials reflect local resources and craftsmanship. Qinghui Garden uses “water-ground stone” for pathways, a technique where stones are polished by river currents for a smooth, natural finish. Liang Garden showcases “wood-carved shutters” with auspicious motifs like phoenixes and peonies, while Yuyin Shanfang employs “gray brick vaults” to reduce heat absorption.

Cultural Symbolism: Poetry, Philosophy, and Social Life

Lingnan gardens are living expressions of Confucian and Daoist ideals. The “Eight Sceneries” of Zuiguan Park (a restored Qing-era garden in Liwan District) include “Bamboo Pavilion in Mist” at “Banana Grove under Moonlight”, each tied to classical poems celebrating harmony with nature. Gardens also served as venues for literary gatherings; Liang Garden’s “Star Grass Study” hosted calligraphers like Zhang Weiping, while Keyuan’s “Bamboo Pavilion” was a hub for the “Lingnan School of Painting”, founded by artists Reslian and Juchao.

Religious and folk beliefs are embedded in design elements. The “Nine-Dragon Screen” in Qinghui Garden symbolizes imperial authority, while Yuyin Shanfang’s “Lotus Pond” represents purity in Buddhism. Even utilitarian features like “rainwater channels” in Liang Garden are carved with lotus patterns, transforming functional infrastructure into art.

Modern Adaptations: Preservation and Evolution

Today, Lingnan gardens balance heritage conservation with contemporary needs. The Guangdong Folk Art Museum in Liang Garden hosts traditional puppet shows and tea ceremonies, while Yuyin Shanfang collaborates with artists to create installations using recycled materials. Guangzhou Cultural Center, a 2023 addition to Haizhu Lake, reinterprets classic motifs like “moon gates” in glass and steel, attracting over 10,000 visitors daily during peak seasons.

Urban planning initiatives, such as the “Lingnan Garden Revival Project”, have restored over 200 historic gardens since 2023, using 3D scanning to document structural details. Digital tools also enhance accessibility; the “Virtual Yaozhou” app lets users explore the Southern Han Dynasty garden via augmented reality, overlaying historical maps onto modern streets.

Guangzhou’s Lingnan gardens are more than architectural relics—they are dynamic spaces where history, art, and ecology converge. By preserving traditional techniques while embracing innovation, these gardens continue to inspire awe and foster community, ensuring their relevance in a rapidly changing world.